It is useful to envision the interplay of military tactics and technics that create the “shape” of warfare as being like the metagame of a competitive videogame. By the “shape” of warfare, I mean what it actually looks like when cohesive groups of men contest each other in lethal violence at large scales. In 1400 AD, the “shape” of warfare was blocks of pikemen attempting to weaken or at least distract opposing blocks of pikemen so that they could be flanked and destroyed by heavy cavalry, big men on big horses with heavy armor and heavy weapons. The pike-armed footman was used because the previous style of footman, arranged in a shield-wall with a shorter spear and a large shield, proved vulnerable to being destroyed by a frontal charge of heavy cavalry. By 1500, the shape of warfare had changed again. It was realized that equipping footmen with seven-foot halberds instead of eighteen-foot pikes provided an advantage when contesting pikes (the head of a halberd can easily manipulate the end of a pike) while not giving up the advantage of a two-handed polearm against a direct frontal charge of cavalry. Incidentally, the switch from shields to polearms made the infantry uniquely vulnerable to bowmen, but bowmen were in normal conditions especially vulnerable to cavalry. This is what is meant by a “metagame” if you are unfamiliar with the term. It is not dissimilar to rock-paper-scissors, tactics which have both advantages and drawbacks in dynamic tension with each other. Technological development can upset this balance, leading to temporarily dominant tactics and counter-innovation, though often the “meta” can stall for a very long time. The shield-wall warfare used throughout the Dark Ages was fundamentally the same Roman “all-infantry” tactic introduced by the Marian reforms over a thousand years earlier, and may have well persisted to this day were it not for the innovations that led to the “meta-breaking” Norman cavalry.

So what is the shape of warfare today? First we need a brief and inadequate sweep through history, and I’ll begin in the 1700s rather than provide a quick rundown of warfare from the Neolithic. The 1700s saw innovations in the fire rate and accuracy of muskets that made cavalry less viable. The vague “rock-paper-scissors” was that artillery could destroy infantry, cavalry could attack exposed artillery, and infantry could destroy cavalry and other infantry. When you have a strategy that does two things at once, it’s going to become predominant. The 1700s saw a lot of line warfare. It was fairly “boring'“ from a military historian’s perspective. Then Napoleon broke the meta of warfare. He realized that cavalry could defeat infantry if infantry had been “softened up” by an artillery bombardment. His military success was based on mobile artillery and cavalry; horses pulling small cannons at higher speeds into good positions to fire on infantry, which could then move away before enemy artillery, heavy artillery with long range, could zero in on the light guns. After the light artillery was done softening up the enemy infantry, they could be charged with cavalry. Infantry does not get many shots off against cavalry. How far can a horse travel in the twenty seconds it takes to reload a musket? It took very disciplined infantry to defeat cavalry (not to mention the bayonet, turning the gun into a pike, but this was not as “obvious” as it sounded because it required metallurgical refinement for lighter barrels; an older arquebus would’ve been far too heavy if lengthened into a polearm), and reducing enemy discipline and cohesion with a little barrage made them vulnerable to cavalry again. Obviously everyone else picked up on this; Napoleon redefined 19th century warfare, which is considered pretty “exciting” to study. Lots of mobility and exciting charges and repositioning and so on. The sort of warfare where tactical genius is made more manifest. As opposed to say, the Dark Ages, where Cnut and Edmund Ironside spent months maneuvering identical armies that fought with identical tactics around without offering direct battle because both were far too smart to get outmaneuvered into a position where one shield wall could gain a decisive advantage on the other.

At the end of the 19th century, smokeless powder and the Lewis gun were invented. If you look at the iron sights on rifles from the late 1800s, you will notice that they had “volley sights” on them that allowed the weapon to be sighted for up to 2000 meters. The default assumption at the time was that warfare in the future would look like it did already, just with longer ranges. 19th century line warfare, but with blocks of infantry standing a mile away from each other, engaging in indirect fire at the expected location of the opposing force. In hindsight, it sounds ludicrous. But most predictions of future warfare today smell to me like this same nonsense. In fact, the current war in the Ukraine was engaged in on at first similar assumptions.

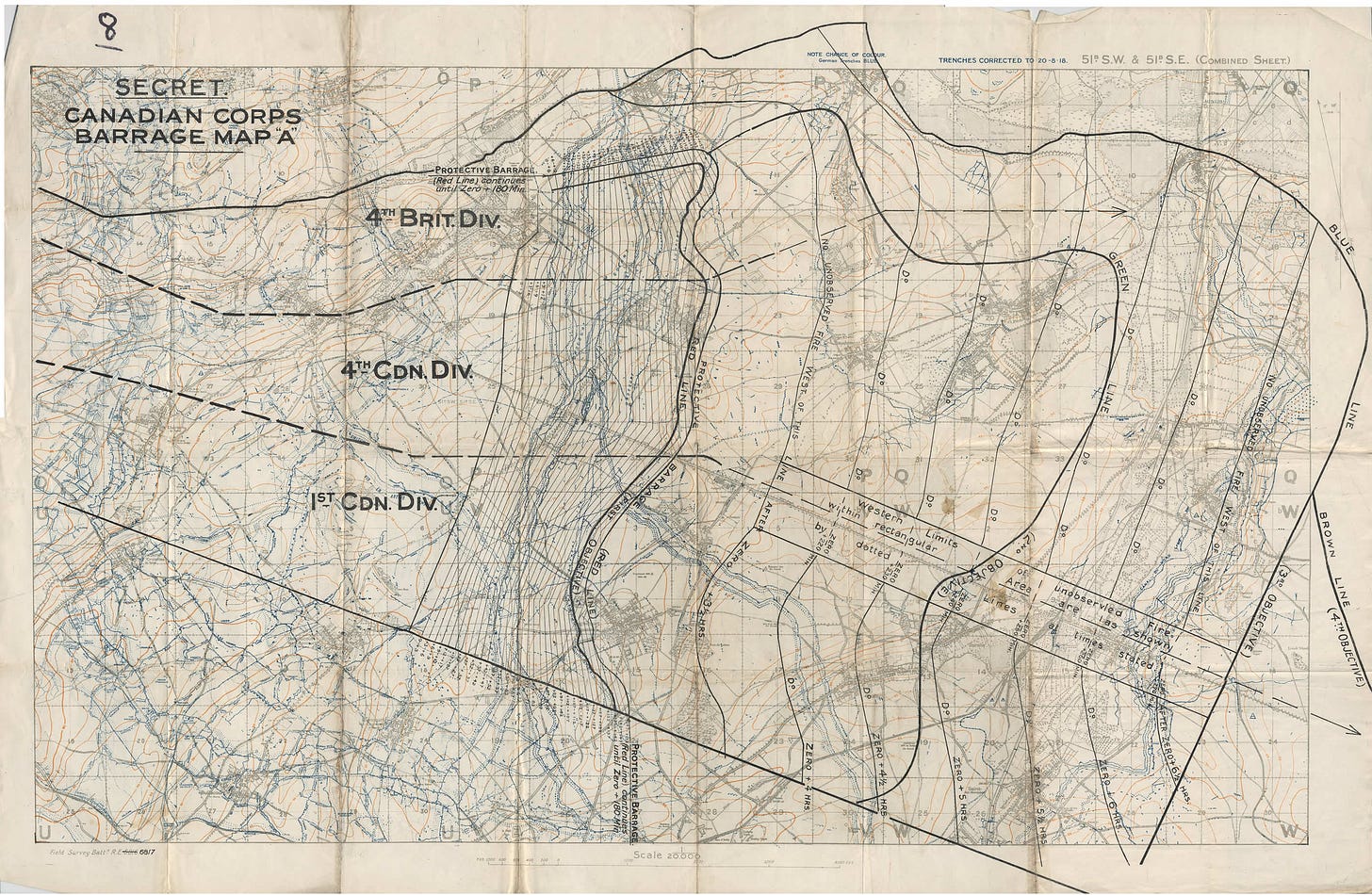

Well, we will come back around to this. World War One was infamously a stalemate in which defensive tactics predominated. The lethality of the water-cooled machine gun, which could fire uninterrupted as long as a man could feed it ammunition, forced infantry into cover; newfound improvements in artillery forced infantry to entrench. This warfare became a stalemate of attrition despite the best efforts of generals on both sides to “restore movement”. Contrary to what is depicted in film, the first lines of enemy entrenchment were not all that difficult to break. Artillery would be immaculately calibrated to engage in a “creeping bombardment” of enemy positions that forced their infantry to shelter deep in their trenches, allowing your own troops to advance. The bombardments were intended to lift exactly when one’s own infantry reached the enemy trench. Too soon and the enemy infantry could man their machineguns before you reached them, too late and you bombard your own forces. The precise calculations required to achieve this were nothing short of a work of art. Looking at a WWI-era artillery firing map is to appreciate a marvel of Faustian warfare; one easily apprehends the colossal, almost unimaginable advantage the European had over other nations at this time.

But this was still not enough to break the stalemate. The enemy would have firing tables with which they could hit their own positions with far greater accuracy than they could manage against an opposing force. Infantry that took the first line of trenches would find themselves under incredibly accurate bombardment, facing a similar situation in attempting to take the second line of trenches, but without any line of supply or reinforcement, and without accurate artillery support to cover their advance. If you remember the metagame I said before, the obvious solution is to use heavily armored cavalry which moves too quickly for opposing artillery to dial in on, but can resist fire from infantry. The horse could not stand against the machinegun, but a tank could. Motorized vehicles were still in their infantry as a school of technics but there was suddenly a deadly need for a cavalry that could resist small-arms fire while moving fast enough to generally avoid getting hit by artillery.

At the end of WWI, the tank became the cutting edge of warfare. A mechanized offensive could break all the way through to the enemy rear, with infantry following behind to exploit the breakthrough. Several political and logistical factors prevented the Central Powers from adapting to this new tactic and technology; by the Second World War, it became clear that the balance of tactic in warfare had shifted from defense to offense. Again, I oversimplify things, air power also emerged during this time, which should itself be considered a form of artillery, of very long range and man-guided targeting, but I digress. The fundamental shape of warfare in WWII prevailed until 2022, nearly eighty years. The emergence of new technologies and the fact that most wars involved counterinsurgency operations and attempts to protect civilians in the name of human rights should not occlude this fact, though “behind the scenes” the shape of warfare changed as much as it had when the Lewis gun was invented.

In WWII, aiming a field mortar, let alone a full sized gun, at a moving column of tanks was a losing proposition. You might get lucky and hit some. But on the whole, the tanks are going to make it to your position before you can destroy enough of them. Once they get in sight, they can fire directly on your guns, not unlike early modern cavalry descending on a near-helpless cannon emplacement with longer distances. Immense improvements in surveillance and information technology changed that. Artillery is queen of the battlefield once again, because unbiquitous surveillance and computer-assisted targeting allow full-size artillery pieces to lay accurate fire on mechanized offensives, lay accurate fire on them as soon as they come into range all the way up to your own position. Theoretically, that is what air power is for. Your bombers and guided missiles are supposed to destroy enemy artillery and then you can attack with tanks again. This was official doctrine until 2022. It is still official doctrine in the US, but not in Russia anymore.

What happened? In 2022, Russia began a flawlessly planned and executed WWII style blitzkrieg. Their bombers flew in, blew up Ukrainian artillery like they were supposed to, and their mechanized offensive took half the country, up to Kiev, in a matter of days. Not only that, but the Ukrainian air force was destroyed down to the last antiquated MiG. Russia had complete and total air supremacy; establishing this was doctrinaire “modern warfare”, i.e. WWII warfare. They even threw in a little Fallschirmjager drop with no tactical or strategic objective that ended up completely destroyed. Cargo-cultism, or just a nihilistic appreciation of irony? And then Russia’s jets started getting shot out of the sky by air defense. Ukraine pulled up extra WWI tube artillery from the west of the country, and with satellite surveillance, started raining incredibly accurate fire on the overextended Russian advance, which forced them to retreat more or less to where the lines are today. And then, with artillery now the supreme weapon of war once again, and helicopters and jets fearing to venture into enemy airspace, the Russians learned their lesson and started digging trenches like it was 1914 again. Because it is, in fact, 1914 again.

Ukraine did not learn a lesson from its temporary victory, or the theater kids in the State Department who give Ukraine its orders did not learn the lesson, and continued to attempt mechanized assaults into Russian fortifications like it was 1943, with the now-predictable result that their tanks were cut to pieces by artillery. Western hype over Leopard and then Abrams tanks shows that the lesson was truly not learned. Show me a tank that can take 155mm and I will show you something capable of reestablishing mobility. But materials science speaks against this as a possibility. All the development that went into “active armor” and rocket defense, and the noble tank ends up helpless against a dumb shell from a piece of WWI tube artillery aimed using google maps and a computer program that runs on a washing machine chip. Well, Vae Victis. What is noble is what wins.

Much today is made out of the potential of drones, especially drones flying around in a swarm and destroying infantry. I understand it on a visceral level; getting hunted down by a robot piloted by a kid with an Xbox controller a hundred miles away sounds scary. But infantry is not the problem that has caused warfare to become warfare of attrition. It is primarily artillery, including long-range guided missiles, and secondarily air defense. Long-range missiles are too expensive to use against anything but the highest value targets; enemy ships, fuel depots, munitions depots that store a lot of valuable missiles, airport hangers full of jets, and command centers. Nobody is really fighting modern warfare, because nobody is really using drones en masse. Looking at drones currently in production, the best option appears to be the Shahed; ideal because of its low cost rather than its power. It has a two-stroke engine smaller than the engine on a dirt bike, a sim card, a wing, and an explosive payload. It cannot cost more than $20,000 to produce, and this could likely be cut down to less than 10,000 with the efficiencies of true mass production. At this number, Honda Motor Corp on its current operating budget could crank out 10 million of them per year, which would also represent 1/7 of the US defense budget. How the Shahed works now is that its operator gives it a latitude and longitude, and then it flies itself there with the same GPS technology your cellphone uses and crashes into the coordinates. Right now it is sort of an autonomous artillery. How it could easily be repurposed to work is adding a camera and a cheap computer that runs a simple AI, so that it goes to approximate coordinates, looks for anything that looks like an artillery piece, and then flies straight into it and blows up. Air defense is expensive and complicated to produce. Mass-produced drones could easily blow through enemy air defense and deny artillery capabilities. Then you have movement again, at least under your own air defense. If Russia developed these manufacturing capabilities, it could be in Kiev as soon as it could field enough drones. If both sides begin using them, the balance may shift back to bombers. Destroy air defense and artillery with drones, and planes can rule the skies again. Something like WWII warfare may be achieved, depending on how well tanks can stand up against a Shahed’s payload. If they can’t, back to WWI again, with drones then being used to attack infantry and clear trenches.

Again, this is a scenario where we have two opposing sides each fielding between 1 and 10 million cheap, autonomous kamikaze drones. Most man-portable anti-aircraft weapons cost more per shot than a Shahed, are harder to manufacture, and have too low a rate of fire to deal with a “massed bombardment” of k-drones. What I mean by that is a near-simultaneous strike on a target or target area by a dozen-plus k-drones at once. Rather than extremely cool million-dollar roadrunners, which are worth spending an AD missile on, Palmer Lucky should be using every shady arms industry contact he can find to get his hands on a Shahed, reverse engineer it into mass-production and improve its autonomous targeting. Actually, one can now buy a chinese-clone Shahed on AliBaba for $50,000, a price which I’m sure reflects low production volume and a very healthy profit margin. But of course the idiotic leadership in the USM would never sign off on such a thing, and even futuristic tech bro defense contractors might turn up their nose at the prospect of manufacturing a flying two-stroke lawnmower with a smartphone and a bomb inside it. Interestingly, though I’ve been saying this for a long time and took a long time to write this article, Ukraine’s top general was recently fired for essentially telling Zelensky that his army needed the manufacturing ability to make a million Shaheds, and that he needed it tooled up in six months to avoid defeat. Clearly he has come to the same conclusion as I have, that the fancy “cutting edge” tech is just not that useful in the current metagame, and he is unwilling to spend the entire male population and half of the female population of Ukraine in what the Russians wryly refer to as “meat assaults”.

This new shape of warfare is theoretically possible today, and the first military force to figure it out is going to have the potential to be completely dominant for a few years. When both sides are using this type of warfare, war’s shape might change completely. A Shahed is cheap enough that attaching a frag payload to it and sending it to look for an infantry squad makes attritive sense. First order for drone assaults will be to destroy artillery, second to destroy vehicles, and third to clear entrenchments or other defensive positions of infantry. We can imagine a battlefield in which Shaheds are constantly flying over enemy territory, near and behind the front lines, ready to throw themselves at anything that looks like a vehicle, and failing that, anything human-shaped, or anything that looks like humans could be hiding in. Many will be wasted on fake targets designed to trick the algorithm, but even fakes require vulnerable people and real vehicles to ship them in and set them up. The “front lines” become a porous wasteland that will be many miles across; potentially a drone’s entire range across. Long range missiles and air defense will duel each other from across this range, attempting to strike supply depots, manufacturing, and hangars, which will become progressively more well-hidden and decentralized.

Now here’s the thing. The calculus that lends one to filling the skies with Shaheds requires that the drones be cheap. Undoubtedly they will be refined from “flying lawnmower”, but there is one very big sticking point and it’s optics. Good optics are expensive. Current drone footage from the current war shows grainy low-res optics, and these are attached to even more expensive drones than will be used in my scenario. The current Shahed doesn’t have a camera at all. Optics are a materials science and manufacturing sticking point. Go look up what good night vision goggles, milspec ones, will cost you. Given current technology, it seems that cheap mass-produced drones, ones like the Shahed that are flying in a straight line, will be able to target things the size of a car, a trench, a machinegun emplacement, but not the size of a man, and especially not a man who is trying to hide. Cheap electric helicopter drones of the sort that are seen dropping grenades on infantrymen in the current war fly very close to the ground, and can see individual infantrymen, but they do not have much range, and are vulnerable to small arms, particularly if an infantry squad is expected to carry a shotgun or two. They work well in a rifle battle, when they can be sent towards an enemy trench a hundred yards away, but do not work so well across the vast no-man’s land that longer-ranged k-drones will create. If drones become complex enough to spot, hunt, and kill individuals and small groups, they become too expensive to be worth using in this manner. It may be possible that small teams of elite infantry will be able to cross no-man’s-land, largely invisible to drones, and attack the enemy in traditional combat; this would be made more possible by the fact that longer-range rocket and missile bombardment will force points of logistical interest to decentralize, to hide and become smaller and individually less-well defended.

Warfare might then take the form of highly mobile and elite soldiers battling each other in skirmishes under a “screen” of drone exchange that denies the use of armor, of artillery, of manned air power, in attempts to capture or destroy sites of strategic importance, slowly degrading the opposing state’s capability to fight. Equally likely, barring the introduction of new technologies, warfare will become war of attrition once again, no side able to put their boots on enemy soil to enforce their will without enormous expenditures of men, material, and capital. At this point, the decapitation strike becomes tempting, and spy networks and computer security come into play in order to put a missile on enemy leadership. In medieval times, killing the enemy king often removed the entire cassus belli from his army, in which case they would immediately return home. The central administrative state that every nation on earth today has adopted is a different story. Decapitating a headless administrative bureaucracy is easier said than done. It would require many, many assassinations, enough to make each individual member of the elite decision-making apparatus feel endangered enough to change the class’ consensus on continued war; there is also a MAD element to decapitation strikes, in that he who orders one is likely to eat one sooner or later. Assassination of political leaders as open warfare tactic is not a cat that said leaders want let out of the bag. One might as well skip straight to nuking the enemy capital.

Anyway, this near-term prediction relies on continuing technical prowess in manufacturing. If technical prowess and globalized supply chains decline, as they did at the end of the Bronze age, and in the late Roman Empire, war will change once again, and in unpredictable ways. War in the course of building an empire in Africa with a small force will have quite a different shape, and deserves not just one but many posts and ongoing discussion.

As an addendum, the future of infantry combat is probably the man-portable flak cannon. The US Army developed, a few years back, an airburst grenade launcher that sighted range and told the grenade to explode at that range. The reason for its abandonment was the intelligence of the average G.I. More elite soldiers of higher quality found the weapon extremely useful- it’s still I believe in limited deployment.

A similar weapon with a slightly smarter computer would allow infantry to combat low and slow flying drones. A rangefinder tells the grenade when to explode, distance and speed of target, and the sight tells the soldier where to shoot to lead a moving drone, let along destroying other infantry behind cover, which was the original purpose. The software required seems trivial to write compared to air defense software.

Great article! I was unaware of the existence of "volley sights" and the expectation that infantry warfare would be indirect fire at long range - what a good lesson on the foolishness of predicting the future based on the past.